The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 83) is a barred spiral galaxy located approximately 14.7 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra. With an apparent magnitude of 7.6 and an apparent size of 12.9 by 11.5 arcminutes, it can be observed in small and medium telescopes. The Southern Pinwheel is catalogued as NGC 5236 in the New General Catalogue. It is one of the brightest and nearest barred spiral galaxies in the sky.

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is a grand design spiral galaxy with an isophotal diameter of 118,000 light-years. More recent sources give the galaxy a diameter of only 50,000 light-years. M83 was given the morphological type SAB(s)c, indicating that is a weak-barred spiral galaxy (SAB) with a pure spiral structure (s) without a ring and loosely wound spiral arms (c).

The bright central region of M83 contains a supermassive black hole. Many barred spiral galaxies have highly luminous central regions, and the Southern Pinwheel is no exception. This happens because the central bar channels gas toward the galaxy’s core and the gas is then used to form new stars. Like many other barred spirals, the Southern Pinwheel is classified as a starburst galaxy. It is undergoing more rapid star formation than the Milky Way, especially in its central region.

This Hubble image shows the scatterings of bright stars and thick dust that make up spiral galaxy Messier 83, otherwise known as the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy. One of the largest and closest barred spirals to us, this galaxy is dramatic and mysterious; it has hosted a large number of supernovae and appears to have a double nucleus lurking at its core. Image credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA); Acknowledgement: William Blair (Johns Hopkins University) (CC BY 4.0)

Messier 83 was nicknamed the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy because of its resemblance to Messier 101, the Pinwheel Galaxy, located in the northern constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear). Like its northern counterpart, M83 appears face-on and has well-defined spiral arms. M83 is slightly brighter than the northern Pinwheel but appears much smaller. It is sometimes also called the Thousand Ruby Galaxy and the Seashell Galaxy.

Like its larger namesake, the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is experiencing bursts of star formation as a result of interaction with a smaller neighbour. Astronomers believe that M83 interacted with the peculiar dwarf galaxy NGC 5253 in the past. The regions of the most intense star formation lie along the leading edge of M83’s spiral arms, where astronomers have detected many young stellar groupings formed from the surrounding gas and dust clouds.

The smaller irregular galaxy NGC 5253 lies in the neighbouring constellation Centaurus. It is a member of the M83 Subgroup of the Centaurus A/M83 Group of galaxies. The dwarf starburst galaxy is 27,300 light-years across and has an apparent magnitude of 10.9. It lies 10.9 million light years away. It was discovered by William Herschel on March 15, 1787.

Nicknamed the Southern Pinwheel, M83 is undergoing more rapid star formation than our own Milky Way galaxy, especially in its nucleus. The sharp “eye” of the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) has captured hundreds of young star clusters, ancient swarms of globular star clusters, and hundreds of thousands of individual stars, mostly blue supergiants and red supergiants. The image, taken in August 2009, provides a close-up view of the myriad stars near the galaxy’s core, the bright whitish region at far right. WFC3’s broad wavelength range, from ultraviolet to near-infrared, reveals stars at different stages of evolution, allowing astronomers to dissect the galaxy’s star-formation history. The image reveals in unprecedented detail the current rapid rate of star birth in this famous “grand design” spiral galaxy. The newest generations of stars are forming largely in clusters on the edges of the dark dust lanes, the backbone of the spiral arms. These fledgling stars, only a few million years old, are bursting out of their dusty cocoons and producing bubbles of reddish glowing hydrogen gas. The excavated regions give a colorful “Swiss cheese” appearance to the spiral arm. Gradually, the young stars’ fierce winds (streams of charged particles) blow away the gas, revealing bright blue star clusters. These stars are about 1 million to 10 million years old. The older populations of stars are not as blue. A bar of stars, gas, and dust slicing across the core of the galaxy may be instigating most of the star birth in the galaxy’s core. The bar funnels material to the galaxy’s center, where the most active star formation is taking place. The brightest star clusters reside along an arc near the core. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) (PD)

NGC 5253 is a blue compact galaxy (BCD), a small galaxy that has large clusters of massive, hot young stars. Blue compact galaxies do not have a uniform shape because they are formed of star clusters.

The central region of Messier 83 is quite unusual. Like our neighbour, the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31), M83 appears to have a double nucleus. The feature was discovered by an international team of astronomers using the Gemini South telescope at the International Gemini Observatory in the 2000s.

The double nucleus does not necessarily mean that the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy has two black holes at its core, but that the single supermassive black hole in the galaxy may be ringed by a disc of stars that orbit around it, creating the appearance of a dual core at the galaxy’s centre. A double circumnuclear ring has been detected in the galaxy’s central region. If the galaxy does contain two black holes, they are expected to collide in about 60 million years.

This photo shows the central region of a beautiful spiral galaxy, Messier 83 , as observed with the FORS1 instrument at VLT ANTU . It is based on a composite of three images, all of which are now available from the ESO Science Data Archive. Credit: ESO (CC BY 4.0)

The galaxy’s visible nucleus is off centre, and astronomers have suggested that this may be the result of Messier 83 having absorbed a small satellite galaxy in the past. The nucleus may be what is left of the smaller galaxy’s core. It is offset from the true dynamical nucleus by approximately 200 light years.

The central bulge of M83 consists of older stars. M83 contains around 3,000 star clusters. Some of them are less than 5 million years old. The brightest clusters are found along an arc near the galaxy’s centre.

Images of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy captured by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) have revealed the remnants of almost 300 supernovae in the galaxy, as well as clusters of new generations of stars forming in the galaxy’s spiral arms. A 2024 study identified 5,724 molecular clouds in the galaxy.

Nicknamed the Southern Pinwheel, Messier 83 (or NGC 5236) is a stunning face-on spiral galaxy located about 15 million light-years away in the southern constellation of Hydra. Its spiral arms are lined with dark lanes of dust and peppered with reddish, star-forming clouds of hydrogen gas. One of the deepest images ever taken of the Southern Pinwheel (combining more than 11 hours of exposure time), this view was captured with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), which was built by the US Department of Energy (DOE) and is mounted on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Numerous background galaxies, which lie much farther away than Messier 83, appear around the edges of the image. Image credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: M. Soraisam (University of Illinois) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin (CC BY 4.0)

Observations with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Victor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile have captured the galaxy’s extended halo and many distant galaxies that appear in the background.

In 2025, observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) led to the first detection of hard ionizing radiation in the nuclear region of M83. While this indicates the presence of an active galactic nucleus (AGN) as the ionization source, it does not definitively confirm it.

The barred spiral galaxy M83 is revealed in detail by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. M83, which is also known as NGC 5236, was observed by Webb as part of a series of observations collectively titled Feedback in Emerging extrAgalactic Star clusTers, or FEAST. Another target of the FEAST observations, M51, was the subject of a previous Webb Picture of the Month. As with all six galaxies that comprise the FEAST sample, M83 and M51 were observed with both NIRCam and MIRI, two of the four instruments that are mounted on Webb.MIRI, or the Mid-InfraRed Instrument, makes observations in the mid-infrared, which spans wavelengths of light very different from optical wavelengths. In this image, the bright blue shows the distribution of stars across the central part of the galaxy. The bright yellow regions that weave through the spiral arms indicate concentrations of active stellar nurseries, where new stars are forming. The orange-red areas indicate the distribution of a type of carbon-based compound known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (or PAHs) — the F770W filter, one of the two used here, is particularly suited to imaging these important molecules. Image credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the FEAST JWST team (CC BY 4.0)

This image was captured by Webb’s NIRCam, or Near-InfraRed Camera. NIRCam makes observations in the near-infrared, which spans wavelengths of light that are just longer than optical wavelengths. Like MIRI, it is equipped with a range of filters that cover its wavelength range of 0.6 to 5 micrometres, including 29 filters specifically intended for imaging. Data collected through eight of those filters were used to complete this impressive image, which picks out light emitted from the wealth of stars that might be obscured by dust at other wavelengths. Even though stars do not emit the majority of their light in the infrared, optical light is much more vulnerable to being scattered by dust than infrared light is, and so infrared instruments like Webb can provide the best opportunities to study stars in regions (like galaxies) that might also contain large amounts of dust. In this image, the bright red-pink spots correspond to regions rich in ionised hydrogen, which is due to the presence of newly formed stars. The diffuse gradient of blue light around the central region shows the distribution of older stars. The compact light blue regions within the red, ionised gas, mostly concentrated in the spiral arms, show the distribution of young star clusters. Image credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the FEAST JWST team (CC BY 4.0)

Centaurus A/M83 Group

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is the brightest member in the M83 Group, a subgroup of the larger Centaurus A/M83 Group. The galaxies in the group lie in the constellations Hydra, Centaurus, and Virgo. The Centaurus A Subgroup is centered on the radio galaxy Centaurus A.

The M83 and Centaurus A groups are sometimes considered to be a single group and sometimes two groups of galaxies. Both groups are part of the Virgo Supercluster, which also includes the Local Group of galaxies and the Virgo Cluster.

Other than M83, the brightest members of the M83 Group are the irregular galaxy NGC 5253, a dwarf starburst galaxy, and the irregular dwarf galaxy NGC 5264.These galaxies have apparent magnitudes of 10.9 and 12.39. NGC 5264 lies in Hydra and NGC 5253 in Centaurus. The irregular galaxy NGC 5408 (mag. 12.2) lies in the same region, in Centaurus, but its membership in the group is uncertain.

The brightest members of the Centaurus A Group are Centaurus A (NGC 5128), the barred spiral galaxy NGC 4945 (the Tweezer Galaxy), and the lenticular galaxy NGC 5102 (Iota’s Ghost) near Iota Centauri. At a distance of around 12 million light-years, Centaurus A is the nearest radio galaxy to Earth. Centaurus A and NGC 4945 are listed in the Caldwell catalogue as Caldwell 77 and Caldwell 83. Both galaxies can be seen in small and medium telescopes.

This excerpt shows some of the interesting features in the image of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy taken with the Department of Energy-fabricated Dark Energy Camera, which is mounted on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a Program of NSF NOIRLab. Image credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), D. de Martin (NSF NOIRLab) & M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab) (CC BY 4.0)

Facts

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is one of the brightest spiral galaxies in the sky, along with the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) in the constellation Andromeda, the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) in Triangulum, Bode’s Galaxy (M81) in Ursa Major, and the Sculptor Galaxy (NGC 253) in Sculptor.

Messier 83 was discovered by Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa on February 23, 1752. The French astronomer catalogued the object as Lacaille I.6 and described it as a “small nebula, shapeless.”

M83 was the first galaxy to be discovered beyond the Local Group and the third of all galaxies to be discovered, after the Andromeda Galaxy (Messier 31) and the Triangulum Galaxy (Messier 33). Bode’s Galaxy (Messier 81) and the Sculptor Galaxy (NGC 253) are both brighter and larger than the Southern Pinwheel, but were discovered decades after M83, in 1774 and 1783, respectively.

At the time of discovery, the true nature of the Southern Pinwheel and other galaxies was still unknown. These objects were commonly described as nebulae. It was not until the early 20th century that the American astronomer Edwin Hubble found Cepheid variables in the Great Andromeda Nebula and realized that the “nebula” was much too distant to be part of the Milky Way galaxy. This led to the realization that these objects were, in fact, galaxies.

Southern Pinwheel Galaxy – Hubble and Chandra composite image, credit – optical: ESO/VLT; X-ray: NASA/CXC/Curtin University/R. Soria et al., Optical: NASA/STScI/Middlebury College/F. Winkler et al. (PD)

The French astronomer and comet hunter Charles Messier observed the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy on February 17, 1781, and included it in his catalogue in March 1781. He noted, “Nebula without star, near the head of Centaurus: it appears as a faint & even glow, but it is difficult to see in the telescope, as the least light to illuminate the micrometer wires makes it disappear. One is only able with the greatest concentration to see it at all: it forms a triangle with two stars estimated of sixth & seventh magnitude: [its position was] determined from the stars i, k and h in the head of Centaurus.”

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is the southernmost galaxy catalogued by Messier. It is, however, not the southernmost Messier object. The open cluster Messier 7, also known as the Ptolemy Cluster, lies at declination -34° 47’, several degrees more to the south than M83.

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy hosted six supernovae in the past century. Few other galaxies have hosted so many observed supernovae. The Pinwheel Galaxy (M101) in Ursa Major also hosted six in the last 100 years or so. The Swelling Spiral Galaxy (Messier 61) in the constellation Virgo hosted eight supernovae from 1926 to 2020. The aptly named Fireworks Galaxy (NGC 6946) on the border between Cepheus and Cygnus hosted ten supernova events between 1917 and 2017, and the current record holder, NGC 3690 in Ursa Major, hosted as many as 12 supernovae, all from 1992 to 2024.

American astronomer Carl Otto Lampland discovered the supernova SN 1923A in the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy on May 5, 1923. The supernova had an apparent magnitude of 14.

The supernova SN 1945B was spotted by American astronomer William Liller on July 13, 1945. It shone at magnitude 14.2.

Mexican astronomer Guillermo Haro discovered the supernova SN 1950B on March 15, 1950. The supernova had an apparent magnitude 14.5.

The supernova SN 1957D (mag. 15), a type II supernova detected by H. S. Gates on December 28, 1957, in M83 in 1957, is particularly notable. Astronomers discovered the supernova remnant in radio wavelengths in 1981, in visible light in 1987, and only recently in X-ray. The spectrum of X-rays indicates that there is a pulsar within the remnant. If true, this would be the youngest pulsar known.

SN 1968L was found by J. C. Bennett on July 17, 1968, and classified a type II-P supernova.

Australian amateur astronomer Robert Evans discovered the type Ia supernova SN 1983N on July 3, 1983. The supernova shone at magnitude 11.9. It was classified as a type Ia supernova and later became the prototype for a hydrogen deficient type Ib supernova.

On July 6, SN 1983N became the first supernova from which radio emission was detected when it was observed with the Very Large Array (VLA). The supernova peaked at magnitude 11.54. A year after the supernova event, astronomers detected around 0.3 solar masses of iron in the supernova remnant. This was the first time that researchers found such a significant quantity of the element in material ejected during a supernova event. The progenitor of the supernova is believed to have been a Wolf-Rayet star.

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy is one of the several relatively bright pinwheels in the sky. Others include the Pinwheel Galaxy (M101) and the Little Pinwheel Galaxy (NGC 3184) in the constellation Ursa Major, the Coma Pinwheel Galaxy (M99) in Coma Berenices, and the Sculptor Pinwheel Galaxy (NGC 300) in Sculptor.

Location

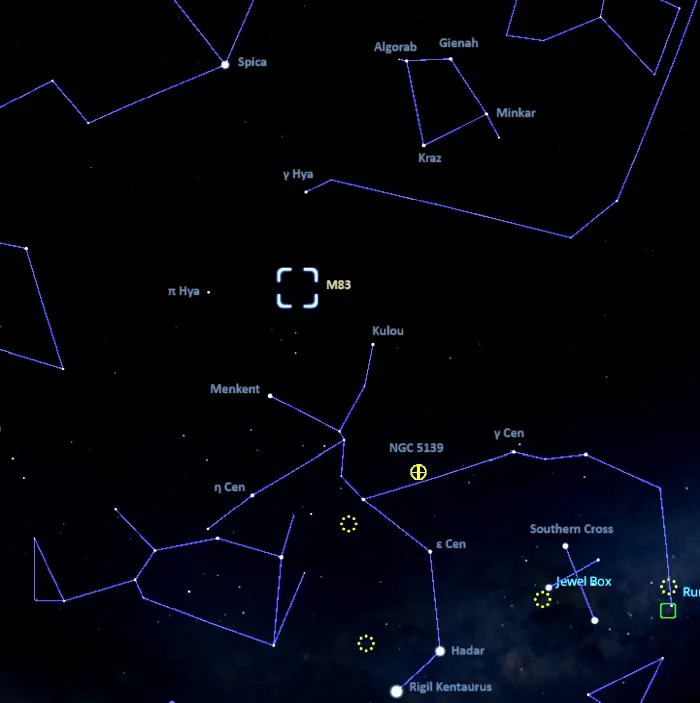

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy lies in the southeastern part of the constellation Hydra, near the border with Centaurus. It is much easier to find from the southern hemisphere because Hydra is a faint constellation, and the northernmost bright stars of Centaurus never appear very high above the horizon for northern observers.

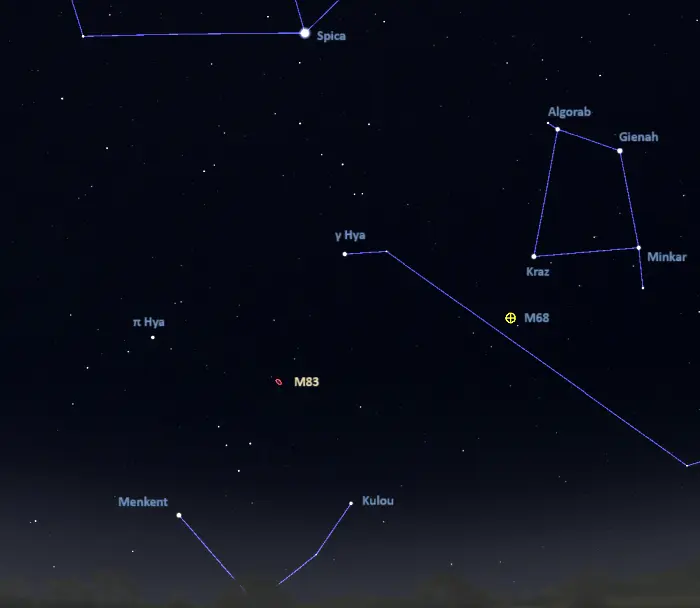

Messier 83 lies near the head of Centaurus, about halfway between Gamma Hydrae and Menkent (Theta Centauri), a little west of the imaginary line connecting the two stars. Shining at magnitude 2.99, Gamma Hydrae is the second brightest star in Hydra. The yellow giant can be located using the stars of Spica’s Spanker, an asterism formed by the brightest stars in Corvus (Gienah, Algorab, Kraz and Minkar). A line drawn from Minkar through Kraz points in the general direction of Gamma Hydrae.

With an apparent magnitude of 2.06, Menkent is the third brightest point of light in Centaurus, after Alpha and Beta Centauri. The orange giant star is easily spotted even in light-polluted skies but can be difficult to identify without the rest of the constellation figure of Centaurus. The slightly fainter Kulou (Iota Centauri) rises just west of it. From mid-northern latitudes, the two stars stay close to the horizon.

The location of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 83) from the northern hemisphere, image: Stellarium

The location of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy (M83) from the southern hemisphere, image: Stellarium

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy appears 6.5 degrees south and 3.15 degrees east of Gamma Hydrae and 3.15 degrees south and 6.20 degrees west of the fainter Pi Hydrae.

The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy can be spotted in binoculars in good conditions.

At declination -29° 52’, Messier 83 never rises for observers north of the latitude 60° N and is best seen from the southern hemisphere. The galaxy never appears very high above the horizon for observers in the northern hemisphere.

The best time of the year to observer the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy and other deep sky objects in Hydra is during the months of April and May, when the constellation rises higher above the horizon in the early evening.

Southern Pinwheel Galaxy – Messier 83

| Constellation | Hydra |

| Object type | Barred spiral galaxy |

| Morphological type | SAB(s)c |

| Right ascension | 13h 37m 00.91920s |

| Declination | −29° 51′ 56.7400″ |

| Apparent magnitude | 7.6 |

| Apparent size | 12′.9 × 11′.5 |

| Distance | 14.7 million light-years 84.50 megaparsecs) |

| Redshift | 0.001721±0.000013 |

| Heliocentric radial velocity | 508 km/s |

| Size | 118,000 light-years (36,240 parsecs) |

| Names and designations | Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, Messier 83, M83, ESO 444- G 081, ESO-LV 444-0810, LEDA 48082, PGC 48082, MCG -05-32-050, MRC 1334-296, IRAS 13341-2936, IRAS F13341-2936, IRAS F13341-2936, 2MASX J13370091-2951567, 2E 3112, 2E 1334.2-2936, 1ES 1334-29.6, CD-29 10465, CPD-29 3793, SPB 225, FAUST 3840, LVHIS 053, Cul 1334-296, RBS 1293, FLASH J133700.23-295204.5, PKS 1334-29, PKS J1336-2951, PKS 1334-296, RX J1337.0-2952, 1RXS J133657.0-295207, SGC 133411-2936.8, HIDEEP J1337-2954, HIPASS J1337-29, SINGG HIPASS J1337-29, NVSS J133700-295155, MSH 13-2-05, PMN J1336-2951, 6dFGS gJ133658.1-294826, TGSSADR J133659.9-295145, QDOT B1334113-293639, PSCz Q13341-2936, TXS 1334-296, VLSSr J133658.0-295147, UGCA 366 |

Images

M83, NGC5236, the `Southern Pinwheel’ galaxy, is a type Sc spiral galaxy in the constellation Hydra. The galaxy has two principal arms and a third, fainter one. There has been a remarkable number of supernovae in M83 within less than a century – at least four since 1923 – compared to the theoretical incidence of one per 300 years. This is still a subject of current research and uncertainty. M83 is 10 million light-years away and thirty thousand light-years across. This picture was taken using color film directly at the Kitt Peak 4-meter telescope in 1973. Image credit: Bill Schoening/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA (CC BY 4.0)

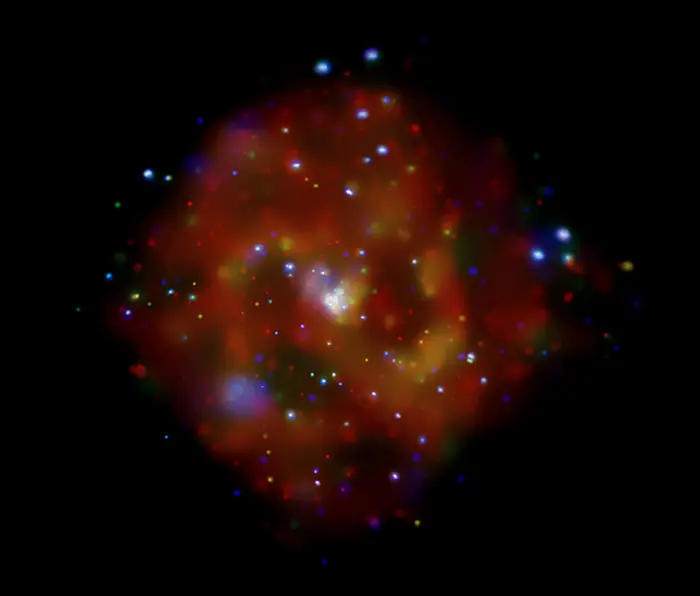

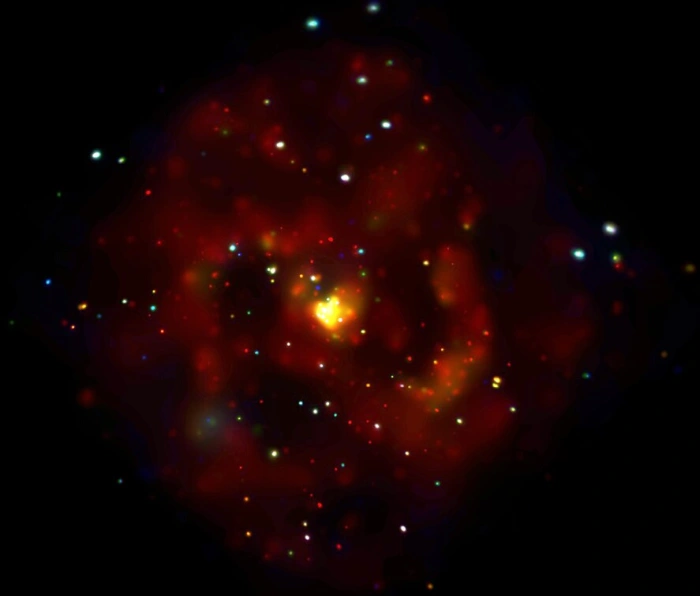

Chandra X-ray Image of M83 This X-ray image of M83 was observed on April 29, 2000 for 13 hours with the Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS). Chandra observations of this spiral galaxy and 3 other nearby galaxies have revealed a possible new class of X-ray sources. These mysterious X-ray sources, marked with green diamonds in the version on the left, are called “quasisoft” sources because they have a temperature in the range of one to four million degrees Celsius. Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/R.DiStefano et al. (PD)

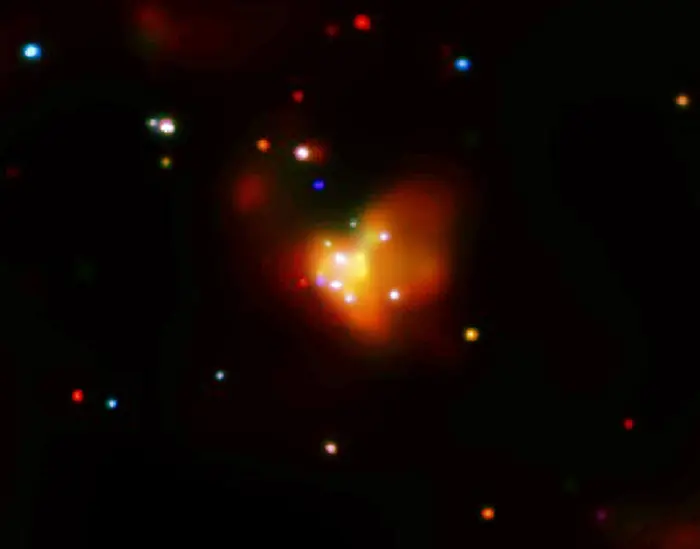

Chandra close-up of M83 Nucleus Chandra’s close-up of M83 shows a bright nuclear region glowing prominently due to a cloud of hot gas and a high concentration of neutron stars and black holes that were created during a burst of star formation that is estimated to have begun about 20 million years ago in the galaxy’s time frame. Credit: NASA/CXC/U.Leicester/U.London/R.Soria & K.Wu (PD)

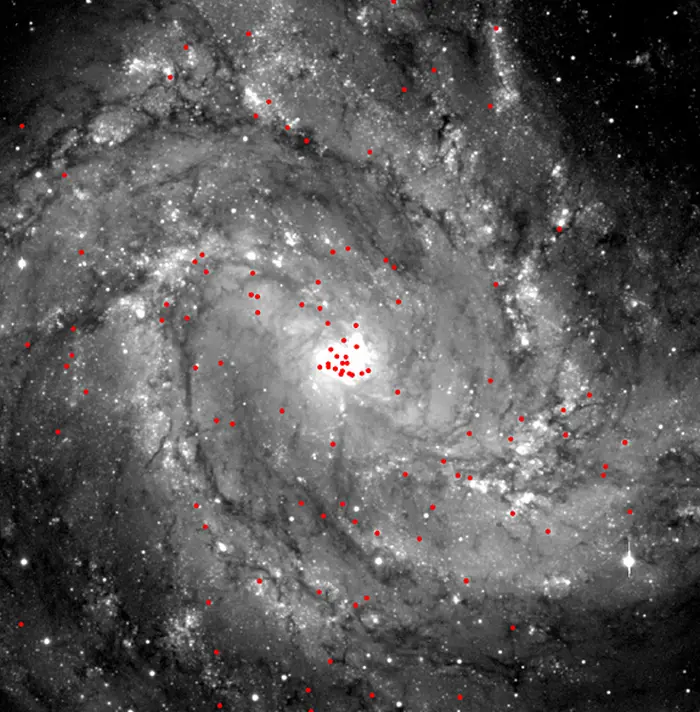

Chandra & VLT Image of M83 The red dots on this image represent X-ray point sources detected by Chandra in M83. The X-ray sources are overlaid on an optical image of the spiral galaxy obtained with ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. Credit: NASA/CXC/U.Leicester/U.London/R.Soria & K.Wu (PD)

The image is a false-colour infrared photo of the nearby barred spiral galaxy Messier 83 . It is based on the combination of three images obtained in the Ks- (wavelength 2.2 µm), J- (1.2 µm) and I-bands (0.8 µm), respectively. Credit: ESO (CC BY 4.0)

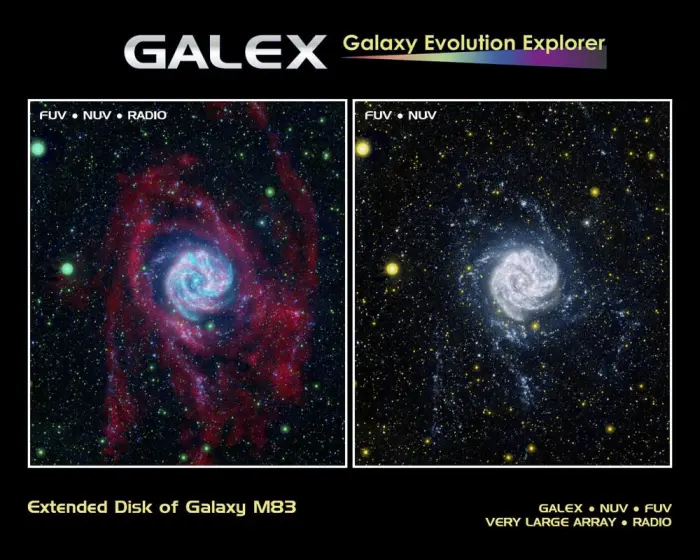

This side-by-side comparison shows the Southern Pinwheel galaxy, or M83, as seen in ultraviolet light (right) and at both ultraviolet and radio wavelengths (left). While the radio data highlight the galaxy’s long, octopus-like arms stretching far beyond its main spiral disk (red), the ultraviolet data reveal clusters of baby stars (blue) within the extended arms. The ultraviolet image was taken by NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer between March 15 and May 20, 2007, at scheduled intervals. Back in 2005, the telescope first photographed M83 over a shorter period of time. That picture was the first to reveal far-flung baby stars forming up to 63,000 light-years from the edge of the main spiral disk. This came as a surprise to astronomers because a galaxy’s outer territory typically lacks high densities of star-forming materials. The picture of M83 from the Galaxy Evolution Explorer is shown at the right, and was taken over a longer period of time. In fact, it is one of the “deepest,” or longest-exposure, images of a nearby galaxy in ultraviolet light. This deeper view shows more clusters of stars, as well as stars in the very remote reaches of the galaxy, up to 140,000 light-years away from its core. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/VLA/MPIA (PD)

The thousands of newly formed stars at the heart of NGC 5236 were imaged with the MUSE instrument, attached to ESO’s Very Large Telescope at Paranal Observatory in Chile. Referred to mostly as the Southern Pinwheel galaxy, NGC 5236 receives its common name from its beautiful spiral arm configuration and its location in a Southern Hemisphere constellation: Hydra. Bright regions of star formation light up thisgalaxy, including the region imaged here, located within the galaxy’s centre. With the right conditions, and commonly within the spiral arms of a galaxy, cold molecular clouds mostly composed of hydrogen gas can collapse and form into brand new stars. In larger clouds, the burning of a new star can create a domino effect, initiating the collapse of the surrounding gas into even more stars. Within a galaxy’s centre however, other processes are at play. The supermassive black hole at the centre of NGC 5236 funnels vast channels of material and matter towards itself; at the same time, it erratically spits matter and large quantities of energy outwards, making the huge amount of star formation around this galaxy’s central region extra messy. Credit: ESO (CC BY 4.0)

This dramatic image of the galaxy Messier 83 was captured by the Wide Field Imager at ESO’s La Silla Observatory, located high in the dry desert mountains of the Chilean Atacama Desert. Messier 83 lies roughly 15 million light-years away towards the huge southern constellation of Hydra (the sea serpent). It stretches over 40 000 light-years, making it roughly 2.5 times smaller than our own Milky Way. However, in some respects, Messier 83 is quite similar to our own galaxy. Both the Milky Way and Messier 83 possess a bar across their galactic nucleus, the dense spherical conglomeration of stars seen at the centre of the galaxies. Credit: ESO (CC BY 4.0)

The vibrant magentas and blues in this Hubble image of the barred spiral galaxy M83 reveal that the galaxy is ablaze with star formation. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA); Acknowledgement: W. Blair (STScI/Johns Hopkins University) and R. O’Connell (University of Virginia) (CC BY 2.0)

Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, processed using archived data from the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA/ESA/Kevin M. Gill (CC BY 2.0)

This image of M83 was captured with the Department of Energy-fabricated Dark Energy Camera, mounted on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a Program of NSF NOIRLab. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), D. de Martin (NSF NOIRLab) & M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab) (CC BY 4.0)

The nucleus of the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, credit: Judy Schmidt (CC BY 2.0)

Chandra’s image of M83 shows numerous point-like neutron star and black hole X-ray sources scattered throughout the disk of this spiral galaxy. The bright nuclear region of the galaxy glows prominently due to a burst of star formation that is estimated to have begun about 20 million years ago in the galaxy’s time frame. The observation revealed that the nuclear region contains a much higher concentration of neutron stars and black holes than the rest of the galaxy. Also discovered was a cloud of 7 million-degree Celsius gas enveloping the nuclear region. The picture that emerges is one of enhanced star formation in the nuclear region that has produced more massive stars, leading to more supernovae, neutron stars and black holes. This activity could also account for the hot gas cloud which shows evidence for an excess of carbon, neon, magnesium, silicon and sulfur atoms. Mass evaporating from massive stars, and the ejecta from supernovas have enriched the gas with carbon and other elements. Hot gas with a slightly lower temperature of 4 million degrees was observed along the spiral arms of the galaxy. This suggests that star formation may be occurring at a more sedate rate in the spiral arms, consistent with the observation of proportionately fewer bright point-like sources there compared to the nucleus. Credit: NASA/CXC/U.Leicester/U.London/R.Soria & K.Wu (PD)