The Perseid meteor shower is an annual meteor shower that occurs from July 23 to August 20. It is one of the most prolific meteor showers of the year. It is associated with the large periodic comet Swift-Tuttle. Best seen from the northern hemisphere, the meteor shower peaks around August 12 – 13 every year. The Perseids are also sometimes called the “tears of St. Lawrence” because they peak near the date of the saint’s martyrdom, August 10.

In 2025, the Perseid meteor shower is expected to peak at its usual time, on the night of August 12 – 13. The best time to observe the meteors is from just after midnight until the pre-dawn hours.

At the peak, about 60 – 100 Perseid meteors may be spotted per hour in clear skies. However, this year many of the meteors will be lost in the glare of a waning gibbous Moon. The Moon will be about 84% full and stay above the horizon from the early evening until the early morning hours. The Perseids will be active until August 23, and it may be better to observe the meteors later this month, when the bright moonlight will not wash out as many of the fainter meteors.

This is a composite of 25 selected frames from an overnight timelapse that captured Perseid meteors. Image credit: Jim Vajda (CC BY 2.0)

The American Meteor Society predicts that the Moon may reduce the number of visible meteors to only up to 20 per hour this year. For this reason, it may be better to observe the meteor shower about a week after the peak. After peak night, the number of visible meteors will decrease, but clear skies may still provide a glimpse at many meteors and the occasional fireball as they streak across the sky.

From light-polluted areas, only the brightest meteors are usually visible in good conditions. While Perseids produce more bright meteors than any other meteor shower, they will not offer as spectacular a show this week as they do on clear, moonless nights. The meteor shower is best seen from locations without artificial lights, away from cities.

Several other meteor showers are active at this time of the year. The Southern Delta Aquariids last from mid-July until late August. The radiant of the faint meteor shower is near Skat (Delta Aquarii) in the constellation Aquarius.

The Alpha Capricornids are active from early July to mid-August. As the name suggests, the radiant lies in the direction of Capricornus. The meteor shower produces much fewer meteors, but is known for the occasional slower-moving fireball. The Kappa Cygnids meteor shower peaks around August 13, but it only appears every seven years.

The Perseid meteor shower is one of the fastest meteor showers visible in the Earth’s sky. Perseid meteors travel up to 58.8 kilometres per second (37 mps).

The meteor shower’s name is partly derived from the Greek Περσείδες (Perseides) or Περσείδαι (Perseidai), a term from Greek mythology meaning “the sons of Perseus.” The name Perseids is pronounced /ˈpɜrsiːɨdz/.

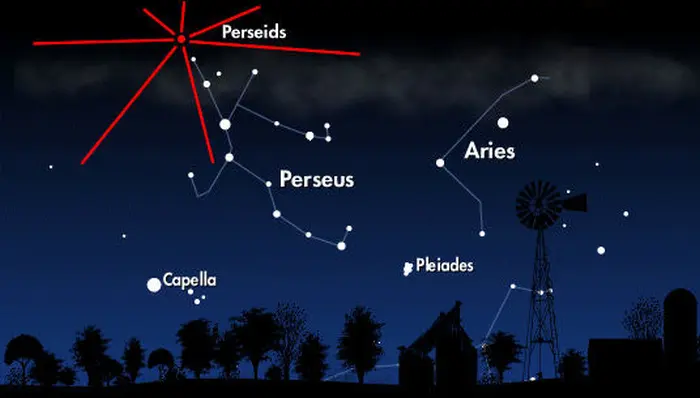

The meteor shower is associated with Perseus because the radiant, the point from which the Perseids appear to come in the sky, is located in the direction of Perseus constellation, near the border with Cassiopeia (the Queen) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe).

The radiant only forms a chance alignment with the constellation. The stars in Perseus are light years away from Earth while the meteors are only about 100 kilometres, or 60 miles, above our planet’s surface.

The Perseid meteor shower is spawned by the comet Swift-Tuttle, formally designated 109P/Swift–Tuttle. Every year, our planet crosses the comet’s orbital path and passes through a trail of debris, causing bits and pieces of the comet to slam into the Earth’s upper atmosphere.

Like all meteor showers, the Perseids represent a spike in the number of meteors, the icy debris and small rocks shed by comets along their orbits. These meteoroids travel at more than 100,000 miles per hour and leave streaks of light as they ignite and vaporize in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Those that are somehow not destroyed in the process fall to the ground and are called meteorites.

Radiant location

Even though Perseid meteors can be seen anywhere in the night sky, they appear to originate from the same region of the sky, located in Perseus.

The radiant of the Perseids lies near the magnitude 7.57 star HD 19557 in the constellation Cassiopeia. The nearest bright star to the radiant is Miram (Eta Persei). Miram can be found using the bright stars of Cassiopeia’s W. A line drawn from Gamma Cassiopeiae, the central star of the W, through Ruchbah (Delta Cassiopeiae), points in the direction of Miram. Shining at magnitude 3.79, the supergiant star is visible from areas without too much light pollution.

The location of Perseus and the Perseids radiant, image: Stellarium

On summer evenings, the constellation Perseus appears high in the northeastern sky and makes its way west during the night.

Miram is part of an asterism known as the Segment of Perseus, formed by a curving line of stars between Cassiopeia’s W and Auriga’s Hexagon. Auriga’s Hexagon is formed by Capella and other bright stars of Auriga (the Charioteer) with Elnath in the neighbouring Taurus. It rises after Perseus in the evening and is fully visible by 1 am.

The Perseids usually peak on August 13, but a relatively young dust filament in the trail pulled off Swift-Tuttle in 1865 can provide an early peak the day before, on August 12.

The trail of debris that appears as falling stars to viewers stretches along the orbit of Swift-Tuttle and is called the Perseid cloud. The comet has a 133-year orbit and ejects particles as it travels. These particles form the Perseid cloud and have been part of it for about a thousand years.

Direction of the Perseids meteor shower in the night sky. Image credit: NASA (PD)

The Perseids can be viewed from mid-July, with the peak in activity occurring between August 9 and 14, when 60 or more meteors per hour can be seen rushing across the sky. The peak rates of meteors occur in the hours before dawn. Most of the meteors disappear at heights above 80 kilometres.

The Perseid meteor shower is primarily visible in northern latitudes because of the path of the parent comet’s orbit, but it can be seen all across the sky. As the radiant in Perseus barely or never rises above the horizon from locations south of the southern tropical latitudes, observers in the southern hemisphere see significantly fewer meteors than those in the northern hemisphere.

The Perseids are best viewed from dark locations, away from city lights. The meteors are best viewed between the constellation Perseus and the zenith, the point in the sky directly overhead. However, it is not necessary to know where Perseus is located as the meteors appear in all parts of the sky.

The Perseids are easiest to see when the sky is the darkest. This depends on the Moon’s phase, but meteor showers are generally best observed in the hours right before sunrise. The best time to observe the Perseids is between 2 and 4 a.m. when the Earth is facing into the pebble swarm. It is, however, possible to view the Perseids as early as 10 p.m. To take pictures of the meteors, a camera’s ISO (sensitivity to light) should be set to a high number, with very long exposures (30 seconds at the minimum).

The exact days, meteor rate, and intensity of the Perseids’ peak (or peaks) are difficult to predict because they change from year to year. Sometimes there are more bright, large meteors and at other times, smaller ones are more plentiful. This happens as a result of an irregular mass distribution within the meteor shower’s trail.

The Perseids are notable for their fireballs, larger bursts of light and colour that originate from larger pieces of cometary debris. The fireballs can be visible longer than regular meteors. They are also usually brighter, with magnitudes brighter than -3.

The zenithal hourly rate of the Perseids (the number of meteors visible per hour at the peak) differs from year to year. In 1863, it was between 109 and 215 meteors per hour. In 1993, it was as many as 200 – 500 meteors per hour. In 1994 and 2004, the rate also exceeded 200. In 2005, 2007, 2011, 2014, 2018 and 2019, it was below 100. In 2021, it was about 150 meteors per hour.

In 2028, astronomers predict a potential Perseid meteor storm. Meteor storms typically produce more than 1,000 meteors during the peak. The Leonid meteor storms in 1999, 2001 and 2002 produced up to 3,000 meteors per hour.

The Perseid meteor shower can be observed as early as July 23, when one meteor can be seen every hour or so. Over the following weeks, the intensity builds up, and about five meteors per hour can be visible in early August. By August 12 or 13, observers can see between 50 and 80 Perseids per hour, and once the peak period is over, the rate declines to roughly 10 per hour by August 15, and back to only one per hour by August 22.

Perseid meteor shower over Joshua Tree, image credit: Joshua Tree National Park, NPS/Brad Sutton (CC BY 2.0)

Facts

The main radiant of the Perseids is located in the direction of the star Eta Persei. Other major radiants are situated near Chi and Gamma Persei, and minor ones near Alpha and Beta Persei (Mirfak and Algol).

In Greek mythology, the Perseid meteor shower is associated with the Perseus constellation and the myth of Perseus’ conception. It is said to commemorate the time when Zeus, Perseus’ father, visited Danaë, Perseus’ mother, in the form of a golden shower.

The Perseid meteor shower was first documented in Chinese annals, which mention that “more than 100 meteors flew thither in the morning” in the year 36 AD. The meteor shower is mentioned in a number of records in China, Japan, and Korea between the 8th and 11th centuries, but there aren’t very many references to it between the 12th and 19th centuries.

The Belgian astronomer and mathematician Adolphe Quetelet is credited for recognizing the Perseids’ annual appearance. In 1835, Quetelet reported that there was a meteor shower occurring in August, appearing to come from the Perseus constellation.

The comet Swift-Tuttle, the parent body of the Perseids, was discovered independently by two American astronomers, Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, in 1862. Swift spotted it on July 16 and Tuttle on July 19. At the time, the comet was as bright as Polaris (mag. 1.99), the 48th brightest star in the sky.

Swift-Tuttle may have been observed by the missionary Ignatius Kegler (Ignaz Kögler) from China on July 3, 1737. Kegler made eight observations on consecutive nights and provided enough information for astronomers to determine the comet’s positions. British astronomer Brian Marsden used the data to calculate correctly that the comet would return in 1992.

Older Chinese records suggest that Swift-Tuttle reached a magnitude of 0.1 in 188 CE, outshining Rigel, the seventh brightest star. The comet was also likely visible in the years 69 BCE and 322 BCE.

Swift-Tuttle is quite large. With a nucleus 26 kilometres or 16 miles across, it is more than twice the size of the object believed to have caused the demise of the dinosaurs. The comet’s size and the size of the meteoroids it leaves behind are the reason why we see so many fireballs during the peak.

In 1865, the Italian astronomer and science historian Giovanni Schiaparelli was the one to make the connection between Swift-Tuttle and the Perseids. Schiaparelli realized that the comet was responsible for the meteor shower. This was the first time that a meteor shower was positively associated with a comet.

Swift-Tuttle has an eccentric orbit, one that takes it inside the Earth’s orbit at its closest approach to the Sun and way outside Pluto’s orbit when it is at its most distant from the Sun.

The comet orbits the Sun with a period of roughly 133 years. Whenever it passes through the inner solar system, Swift-Tuttle is warmed by the Sun, which causes it to leave fresh debris along its orbital path.

Swift-Tuttle last reached its closest point to the Sun, known as the perihelion, in December 1992. It will reach it again in July 2126. In 1992, the comet was too faint, but, in 2126, it may be visible to the unaided eye.

In 1992, the comet was rediscovered by Japanese astronomer Tsuruhiko Kiuchi. At the time, it was visible in binoculars. In 2126, it may be visible to the unaided eye again. With an apparent magnitude of 0.7, it will outshine the bright Altair in Aquila and Acrux in Crux.

Every year in mid-August the Perseid meteor shower has its peak. Meteors, colloquially known as “shooting stars”, are caused by pieces of cosmic debris entering Earth’s atmosphere at high velocity, leaving a trail of glowing gases. Most of the particles that cause meteors are smaller than a grain of sand and usually disintegrate in the atmosphere, only rarely reaching the Earth’s surface as a meteorite. The Perseid shower takes place as the Earth moves through the stream of debris left behind by Comet Swift-Tuttle. In 2010 the peak was predicted to take place between 12–13 August 2010. Despite the Perseids being best visible in the northern hemisphere, due to the path of Comet Swift-Tuttle’s orbit, the shower was also spotted from the exceptionally dark skies over ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile. In order not to miss any meteors in the display, ESO Photo Ambassador Stéphane Guisard set up 3 cameras to take continuous time-lapse pictures on the platform of the Very Large Telescope during the nights of 12–13 and 13–14 August 2010. This handpicked photograph, from the night of 13–14 August, was one of Guisard’s 8000 individual exposures and shows one of the brightest meteors captured. The scene is lit by the reddened light of the setting Moon outside the left of the frame. Image credit: ESO/S. Guisard (CC BY 4.0)

Perseid meteor shower

| Parent body | Comet Swift-Tuttle (109P/Swift–Tuttle) |

| Radiant | Perseus constellation |

| Radiant – coordinates | Right ascension: 03h 13m |

| Declination: +58° | |

| First record of discovery | 36 CE |

| Dates | July 23 – August 20 (July 14 – September 1) |

| Peak | August 12 and August 13 |

| Velocity | 58.8 km/s |

| Zenithal hourly rate | 100 |

Images

Perseids from Poland, image: Wikimedia Commons/Michal.danes (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Astronaut Scott Kelly posted this photo of the Perseid meteor shower taken from the International Space Station on Instagram with the caption, “Space weather forecast from @ISS: Moonless with a chance of Perseid meteors!” Credit: NASA (PD)

Perseids from Alabama Hills, credit: Flickr Commons/John D. (CC BY 2.0)

Perseids compilation, image credit: Flickr Commons/mLu.fotos (CC BY 2.0)

This is a composite of 7 selected frames from an overnight timelapse sequence that captured the Perseid meteor shower in southwest Ohio. Image: Jim Vajda (CC BY 2.0)